Sheriffs for hire

Sheriffs for Hire: Contract Cities

When Law Enforcement is a Business

The Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department is the largest sheriff’s office in America. In addition to patrolling unincorporated areas, the LASD also contracts to provide law enforcement services for 42 contract cities. Basically, the LASD establishes stations that serve as local police for many of these municipalities, which include places as diverse as Compton, West Hollywood, Lawndale, and Malibu. Many of these cities have been the site of incredible violence from the LASD, including the prevalence of deputy gangs and cases of deputies killing civilians. And, of course, there are racial disparities.

Just a handful of chilling stats, based on LASD use-of-force data and current demographics:

Compton: Black people are 30% of the population, but 47% of LASD victims.

Palmdale: Black people are 12.5% of the population, but 36% of LASD victims.

Lancaster: Black people are 22% of the population, but 25% of LASD victims.

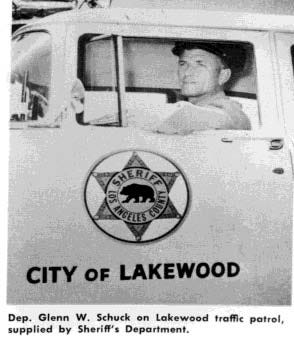

Contract cities exist throughout the country. Usually, they are cities that simply do not have the revenue (or political will, as I will explain) to stand up their own police department. Contract cities were created by design as a way to have the benefits of a municipality with none of the costs associated with the creation of a municipal government. Lakewood, in Los Angeles County, was one of the first cities to implement this model, purchasing all municipal needs – including law enforcement – from the county, spurred in no small part by an explosion of population growth in Southern California after World War II.

Touting Lakewood as a city “without a payroll,” the political movement in favor of incorporating Lakewood was funded in large part by the county utility company, which wanted to keep Lakewood residents as a customer base. The Los Angeles Board of Supervisors similarly decided the “Lakewood Plan” was a good idea as it would allow them to make money by providing services to smaller, incorporated municipalities. Municipalities were encouraged to pick and choose their services as if from a menu. By 1960, there were 26 contract cities in Los Angeles County, and the county became somewhat of a pioneer in this method of policing.

A lot of the motivations for creating contract cities were rooted in protecting business interests, and commentators at the time note that the LASD needed to appeal to the interests of "elite decisionmakers," the city planners and politicians who were invested in keeping taxes and expenses as low as possible. The City of Industry, for example, incorporated for the sole purpose of attracting more manufacturing plants; the local residents in a home for the mentally ill were included to juke the population stats so the area could qualify as an urban center. (Industry is still only about 200 residents, although there are some fake movie-set restaurants.) Other contract cities formed in order to protect their residential planning zones that prevented the construction of multi-family homes and kept the community white. Pico Rivera incorporated in order to avoid property taxes. The concept of contract cities was even cited in the 1967 Katzenbach Commission Report as a way to lower costs and eliminate very small (and presumably inefficient) police departments.

But purchasing services from the county came at a price. Most relevant to law enforcement, contract cities lost the ability to decide for themselves what sorts of services their cities needed. In the case of the sheriff’s office, contract cities had a “sheriff supreme” clause: “It provided that in the event of a dispute between a city and the sheriff over the "level and manner" of police protection, the sheriff had the last word.” So, for example, contract cities could not request particular police services – like more detectives – and instead just got the standard package. In some cases, contract cities wanted more policing or specialized policing to solve specific crimes, but the sheriff was under no obligation to provide that.

Contract cities also faced problems pulling out. In 1958, Norwalk tried to pull out of its agreement with LASD. Then-Sheriff Peter Pitchess (more on him another time) waged political war, pressuring Norwalk leaders to keep the contract with some concessions. Some reports include deputies handing out political pamphlets opposing the creation of a police department. While some theorists suggested that the LASD would improve its services in contract cities to avoid losing the revenue, it’s unclear how that has worked out. There has been, over the decades, more research and reports on the cost of contract policing (especially as to whether those costs are subsidized by the county tax base as a whole), but none on the kind and quality of policing communities want. As a reflection of that, one researcher in the 1970s characterized Los Angeles contract cities as “dynamism, competition, and change taking place within an understandable system geared to an efficient meeting of consumer demands,” only off-handedly admitting that there were problems for “citizens that lack demand articulating mechanisms,” referring to Black and Latinx residents unhappy with the policing quality.

Today, contract cities are still facing the same problem, struggling to pull out of rigid contracts with the LASD that no longer fit the community’s needs. Take Antelope Valley (cities of Lancaster and Palmdale). As part of a contract city for the LASD, residents of the municipality have experienced incredibly cruel and disrespectful policing, including the rigid enforcement of “crime free” housing ordinances, which allows deputies to effectively evict people on mere suspicion of criminal activity. (Under a federal civil rights settlement, the two cities must poll their residents every year on their satisfaction with LASD policing.) And then, in the summer of 2020, two Black men were found dead from hanging. The LASD initially ruled them suicides before agreeing to investigate. In Compton, LASD gangs have operated with impunity, increasing violence, terrifying community members, and killing or severely injuring residents.

The contract cities have expressed their concerns about Sheriff Alex Villanueva’s actions, particularly his rehiring of deputies who were dismissed for violent acts and other misconduct. In a spring 2019 letter, the contract cities also expressed concern over the conflicts between Villanueva and the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors, fearing that Villanueva’s aggressive politicking would shift attention away from policing their communities and would force them to incur additional costs from litigation. (It’s also important to add that the California Contract Cities Association speaks specifically of “our primary obligations to our residents and business owners,” which goes back to the capitalist roots of contract cities. In other words, contract cities were not created with an eye towards rectifying inequality.)

Los Angeles, of course, is far from the only county with contract cities that rely on the sheriff for their policing. In California alone, about 30% of all cities contract with their sheriff for policing. Throughout the country (especially in Arizona, California, Florida, Illinois, Minnesota, Ohio, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington), smaller cities and suburbs rely on the sheriff for policing, which, in many cases, creates a further gap between what community members want (excluding business interests, which do dominate more rural budget discussions) and what they get for their money. The solution, which some communities pursue, is to create their own police force, but it’s important to acknowledge that this is a financial and administrative hurdle that requires the coordination of municipal powers who may not have the same interests. In sum, contract cities are another way sheriffs fall far short of community-controlled policing and create barriers for those seeking change.

Note on sourcing: I tried to link most of the articles I used for this piece, but some are only available on paywalled websites. If you have more questions about sourcing, please let me know!

Other Reading

1. A story out of Maine described some shocking sheriff behavior. My favorite part: despite patterns of wrongdoing by sheriffs – including one who managed to disappear – sheriffs showed up in force to protest legislation that would have created oversight measures.

2. The Southern Poverty Law Center is suing an Alabama sheriff for failure to release information on coronavirus infection numbers within his jail.

3. California Governor Newsom’s new coronavirus-related restrictions and business closures are inspiring another wave of outspoken sheriff objections and refusals to enforce.

4. President-elect Biden had tapped current California Attorney General Xavier Becerra for Secretary of Health and Human Services. I don’t have a lot of opinions about this choice, but I think that the new AG should be someone willing to stand up to sheriffs, especially Sheriff Villanueva in Los Angeles County. For my money, Dennis Herrera, the SF City Attorney, strikes me as the most likely contender. I know him from his lawsuit against a “restorative justice” program being used by big box stores to extort money from people caught shoplifting.