A Few Good Men

A Few Good Men: What makes a sheriff?

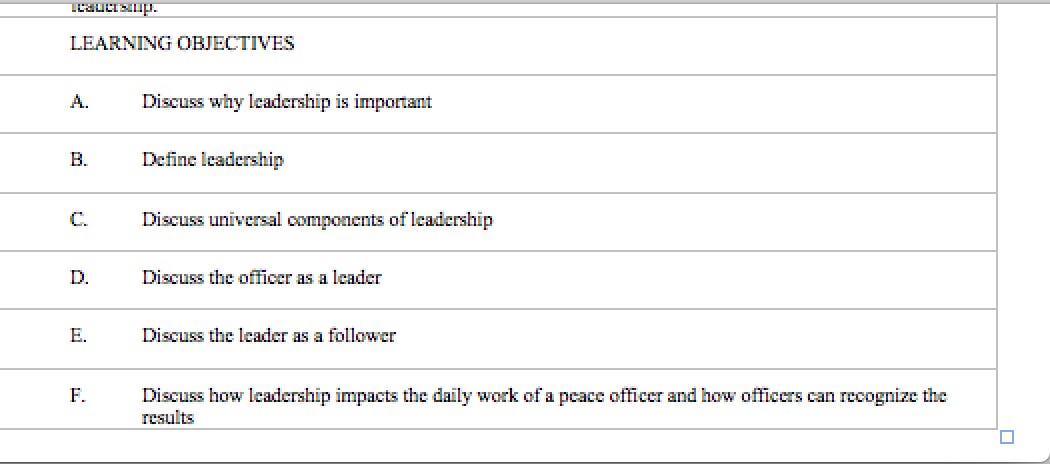

California State Senator Scott Weiner introduced a bill that would remove the law enforcement training requirement from California’s requirements to be sheriff. The requirements were established in 1989 after Michael Hennessee was elected sheriff of San Francisco in 1979…and went on to serve over 30 years. The California requirements are among the most stringent in the nation. Sheriffs in California currently must be “POST certified,” which is just the basic law enforcement training required in many states to be in law enforcement, in addition to some combination of experience in law enforcement and/ or higher education. Gotta take your “Leadership, Professionalism and Ethics Course,” which includes such head-scratchers as described below.

In 2019, one man tried to challenge the California requirements. Bruce Boyer, an anti-immigrant conspiracy theorist, wanted to be the sheriff of Ventura County. The California Court of Appeals shot down Boyer’s case, largely on the rationale of “common sense.” “It does not matter how intelligent you are or if you are acting in good faith,” the court declared in some high-minded rhetoric, comparing sheriffs to plumbers.

In most states, there are very few requirements. The most common one, actually, is that sheriffs cannot “practice law.” Funny enough, this was originally intended to prevent sheriffs from becoming the judge and jury. (Like the time Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gaultieri refused to arrest a white man for shooting a Black man in a parking lot, arguing that the shooter was protected by “stand your ground.”)

Other requirements range from basic (residency and age) to the bizarre but potentially useful. In Alabama, sheriff candidates cannot have been convicted of “treason, embezzlement of public funds, malfeasance in office, larceny, bribery or any other crime punishable by imprisonment in the state or federal penitentiary and those who are idiots or insane.” In Missouri, they must be “capable of efficient law enforcement.”

Most states do not allow people with prior convictions to run for sheriff. In Arkansas, this caused a bit of a problem. Searcy County Sheriff Kenny Cassell, elected in 2010, was charged and convicted by a federal court for “receiving stolen Cornish hens” in 1979 (valued at less than $100) when he was 20 years old. Alas, he was removed from office because of his participation in a chicken heist. The Arkansas Supreme Court confirmed his removal, holding that the chicken heist was an “infamous crime,” and, thus, involved deceit.

But perhaps all was not lost? In 2016, the Arkansas legislature changed the requirement to only bar people who were convicted of misdemeanors “in which the finder of fact was required to find, or the defendant to admit, an act of deceit, fraud or false statement.” Cassell’s lawyers argued that the chickens did not count, (as Cassell didn’t LIE about the chickens) writing in a brief, “Cassell’s guilty plea… merely stemmed from his receipt of chicken chattel, not any active fraudulent or deceitful obtaining of chicken chattel by theft as described in the statute.” He didn't actually steal the chickens, he just held them. What are you supposed to do when people bring you chickens? The district attorney did not allow Cassell to run again.

On the other end of the spectrum, Mississippi Sheriff Paul L Barrett served almost 30 years before being convicted of federal perjury charged in 1995. The New York Times noted that Barrett was “one of four county sheriffs with past convictions in Mississippi” who were re-elected THAT YEAR. The state sheriff association denied all four admission, with the president saying, “We already have enough problems with the Rodney King mess.” (That mess, oh yes.) The Attorney General described these sheriffs as “examples of the fox guarding the chicken coop.” [Insert Cornish hen joke here.)

Interestingly, these sheriffs were caught in another change of laws. The original Mississippi law barred sheriff candidates who were guilty of “bribery, murder, rape, theft, bigamy” or “denying the existence of a supreme being.” In 1992, the state legislature added “federal felonies” to the list.

What did these sheriffs do that was so roguish? One sheriff was convicted of “taking bribes from Drug Enforcement Agents posing as drug dealers to allow them to bring marijuana into the rural county to sell in 1986.” And another was convicted of selling amphetamines. Barrett insisted his crime wasn’t like those guys, even though he retired and spent a year in prison. Actually, Barrett’s crime was pretty much the same as the others. He had received a fancy $15K motorcycle as a “gift,” and then lied to help his “friend” get out of a ticket for having shotguns in his truck while he was in Washington D.C., where that is not allowed. The “friend” tried to get out of the fine by saying he was a sheriff’s deputy, in which case he could lawfully have shotguns.

[If you are confused about that, don’t worry. One newsletter will cover special laws for deputies and guns.]

Meanwhile, The Los Angeles Times Op-Ed page called for the elimination of sheriffs and a reallocation of their responsibilities. The Los Angeles Board of Supervisors received a report on the well-trod territory on methods to remove Sheriff Alex Villanueva. One supervisor suggested that there should be a county police force, with the sheriff running the jail only. But why should a sheriff run a jail? Couldn’t you have a civilian county employee who runs the jail? Imagine, a jail run by someone who isn’t law enforcement? Without the political incentive, this administrator would be inclined to work WITH the BOS, perhaps reducing their budget so as to help other county entities. Rather than a wearisome, political process where sheriffs bully their budgets through, what if, stay with me here, the person in charge of the jail cares more about the health of the community overall?

Other Reading

Jonathon Booth wrote a nice piece about the historical role of sheriffs during and after Reconstruction, specifically parsing out the differences between sheriffs, “slave catchers,” and urban police (which were quickly used to police immigrants). He winds up where I often do, which is rethinking the role of non-urban law enforcement in terms of a defund v. reform strategy. When I talked to someone the other day about sheriffs and the struggle with it comes to defund, they pointed out that perhaps people interested in change should look to the entire structure of counties. Yes! I shouted. We should be thinking about counties. See above.

A new Oregon report found increased jail deaths due to suicide. The author points to the need for more resources in the community, and multiple sheriffs are quoted agreeing that they don’t want to be jailing people who have mental health concerns (even though they are). But, those same sheriffs run jails where they are still using dangerous methods, like restraint chairs, which kill people. Sheriffs seem all to willing to shrug off deaths by suicide as mysterious and unpreventable, but there are proven ways to prevent this. Take this damning statement from the report: “Punitive jail culture rather than clinical best

practices inform jail suicide precautions.” It’s become a bit of a cliché for sheriffs to throw up their hands and say they run “mental health facilities” against their will while bemoaning a lack of resources. But, evidence shows they still aren’t doing basic things! I am not in favor of increasing funding for jails, and people should not be in jail, but reports like this are so frustrating to me because people still aren’t doing the basics that need doing (and don’t require money). Yet, watch those sheriffs use the report to say they need money.