Be a Man

Newsletter for October 19, 2021

Sheriff Alex Villanueva of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department has a new hat – a more cowboy-shaped hat to replace the “outback style” he had previously sported. (Villanueva says he wears the hat to protect his skin; he’s had skin cancer in the past.) He’s also made a point of talking regularly about his “policy change” that will allow deputies to wear hats.

“It looks pretty good,” he said during the Facebook Live announcement, in response to no question while ignoring questions about LASD gangs, COVID vaccines, and multiple investigations into his department.

Villanueva is not alone in adopting the cowboy hat in recent years. Sheriff Doc Holliday of Arkansas (he has since been replaced by another sheriff — no data on the hat policy yet) spent over $26K purchasing hats for the deputies in his department. The sheriffs of both Riverside County (yes, the Oath Keeper one) and Napa County, California, implemented cowboy hat-wearing policies. Sheriffs in Wyoming and Texas banned hats, citing a need for a more professional look. At least one Wyoming deputy resigned. (“I’m not going to change,” he said.)

Last week, I published a story about an Arizona sheriff who is leading a new far-right sheriff movement that seems designed to bring sheriffs and sheriff iconography into the public spotlight. Sheriff Mark Lamb himself is, honestly, a model of that icon. He sports his cowboy hat everywhere. Unlike Villanueva, who prefers a Stetson, Lamb wears one from Justin, a Texas brand known mostly for boots.

Scholar Michael Kimmel argues that the “crisis of masculinity” at the turn of the 20th century – caused by increasing industrialization and the effective Anglo-Saxon conquest/ genocide of the Western frontier – men turned to Western novels and other fictionalized representations of the cowboy as a way to feel manly. This fictional cowboy – embodied by characters like Buck Taylor and Buffalo Bill Cody – was far from the actual work-class, racially diverse set of men who actually drove cattle in the West. (In fact, the word “cowboy” denoted that a worker was lower in status than “cattle men” who owned the herds.) Such cowboys were staples of novels, rodeos, and “Wild West” shows.

The ideal cowboy embodied manly virtues like bravery, integrity, and “sheer nerve.” There was a belief in natural law and natural rights – so while a cowboy might not go to church very often (too feminine) or engage in politics (too sissy), a cowboy would have, as they say, a code. The West in these fictions is a masculine fantasy, not really anti-woman, but anti-feminization. As Kimmel writes:

The vast prairie is the domain of male liberation from workplace humiliation, cultural feminization, and domestic emasculation. The saloon replaces the church, the campfire replaces the Victorian parlor, the range replaces the factory floor.

Cowboys were also very white. The author of The Virginian, widely considered the first Western, was clear that cowboys were “manly, egalitarian, self-reliant, and Aryan.” In some cases, cowboys were depicted as descendants of chivalric knights.

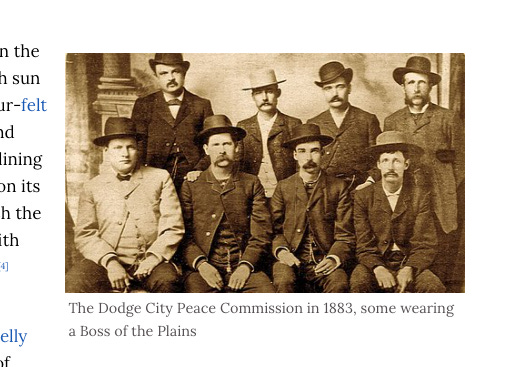

The hat itself traces a similar origin. The first Stetson hat, called the Boss of the Plains hat, was marketed in 1865. It was creaseless and very utilitarian. Not until the explosion of wild west fantasy at the turn of the century did the hat that we now associate with cowboys (or sheriffs) come to be.

At the time the Stetson was invented, a lot of men wore hats, both so-called lawmen and so-called outlaws (there wasn’t much difference between the two). Law enforcement in most of the West was barely different from the vigilante networks I wrote about earlier in Los Angeles and California more generally.

It’s not clear to me when sheriffs specifically adopted cowboy hats as part of their lewk. Photos show some, as above, and there are definitely a lot of mustaches. But many sheriffs at the turn of the century posed hat-less in dark suits, to show their professionalism. As Gustavo Arellano writes, there isn’t a lot of evidence that the cowboy hat was associated with sheriffs in California until around 1932, which is when Sheriff Eugene Biscailuz was sworn in. He wore a Stetson and, in his quest to professionalize the LASD, he got his deputies to wear one too. (To be fair, he had a sort of cowboy vibe before he became sheriff.) But you can see that his hat is also the “boss of the plains” version, or so it seems to my naked eye.

There has been somewhat of a resurgence of the cowboy hat as a symbol in the wake of the new, Trumpian masculinity. Not unlike the turn-of-the-century that Kimmel describes, the rise of Trump coincided with the rise of the Men’s Right Movement, concerns about policing women’s bodies, a revived gun show culture, and, of course, “replacement theory” paranoia. I joke around about Cross Fit, but that’s there too – the idea that men, emasculated in the economy and culture as manufacturing jobs die out, have to exercise in a particularly unpleasant and painful way.

One writer for the Claremont Institute described masculinity thus: “But for the majority of men, purpose is intertwined with masculinity. Men were designed to protect, build, innovate, and care for others.” There’s a bit of an exception made for some men who are less masculine — you are okay — but the argument the author makes is the masculinity is inborn and needs to be revived and taught through specific practices that can only be done, presumably, by other men. A man exhibits “healthy living and true manliness” when he lives courageously, speaks the “truth” and deals with emotions. There are, of course, no real practices prescribed here, just the same drivel that masculine institutions have been saying for centuries. (“Dealing with emotions” reminds me of the rhetoric law enforcement and the military use for dealing with PTSD related to violence — the suggestion isn’t that violence is bad or to be avoided, but that it happens and the negative fallout is, of course, manageable.) It reminds me of the Mulan song.

This brings me back to Sheriff Mark Lamb, who was not a cowboy — he did pest control — but adopted it as a part of a persona – like a version of the Wild West Show – that he uses to political ends.

Policing needs, and always has needed, masculinity to give itself cultural salience – I don’t think this is a novel idea. Masculinity relies on exclusion, which is why movements like the KKK to militias to, yes, sheriffs seek to divide the world into, as the militia movement says, “sheep” and “wolves.” (or “sheepdogs;” I get confused.) This is probably why police unions have such stickiness; they are both an economic effort to retain the dignified trappings of “skilled workers” for law enforcement as well as a fraternal organization that excludes others.

And, indeed, there are now women officers and more officers who are Black (though their numbers are going down). I’m not of a mind that increasing the number of non-white men in an institution changes it, and here’s why: It’s not that an institution excludes women and POC; it’s that the institution ensures those who are different are unequal. Women have always worked in law enforcement – they are assistants, emergency operators, accountants. Black people have also always worked in law enforcement – they were un-free labor used to wash cars, cook food, and, often, act as covert information-gatherers. So, the idea of “diversifying” law enforcement is just a phantom so long as inequality exists.

In the course of my work, I have been interested in how men assert themselves in homosocial relationships. When I reported on prison guards in California, I found shocking levels of harassment and hazing, which included beatings, locking people in cages, dousing people in gallons of water, and wrapping people in barbed wire.

Becoming an officer isn’t much different. There’s an episode of the American Sheriff Network (subscriber-only), a group of new deputies get tased one by one while their supervisors watch and film them. The ostensible purpose is to teach the new recruits how painful electric shocks can be. But the camera focuses on one young man who looks barely 18, and his eyes water as he watches one friend, then another, fall to the ground in a quivering, sobbing, screaming heap. He’s trying to keep up his bravado – he’s on camera after all – but you can see him hesitate. He’s the last one to go. Is it me, or does he look longingly towards the door, at a different fate? But he goes through with the hazing ritual, subjecting himself not just to pain, but pain with an audience. Only the men in the room know what he has gone through, and one day, this boy will do it to someone else, another new recruit, without thinking about why.

This hazing ordeal is something these secret "male" societies have been using for hundreds of years- one would think this was illegal at this point, particularly for anyone enlisted in any arm of enforcement!