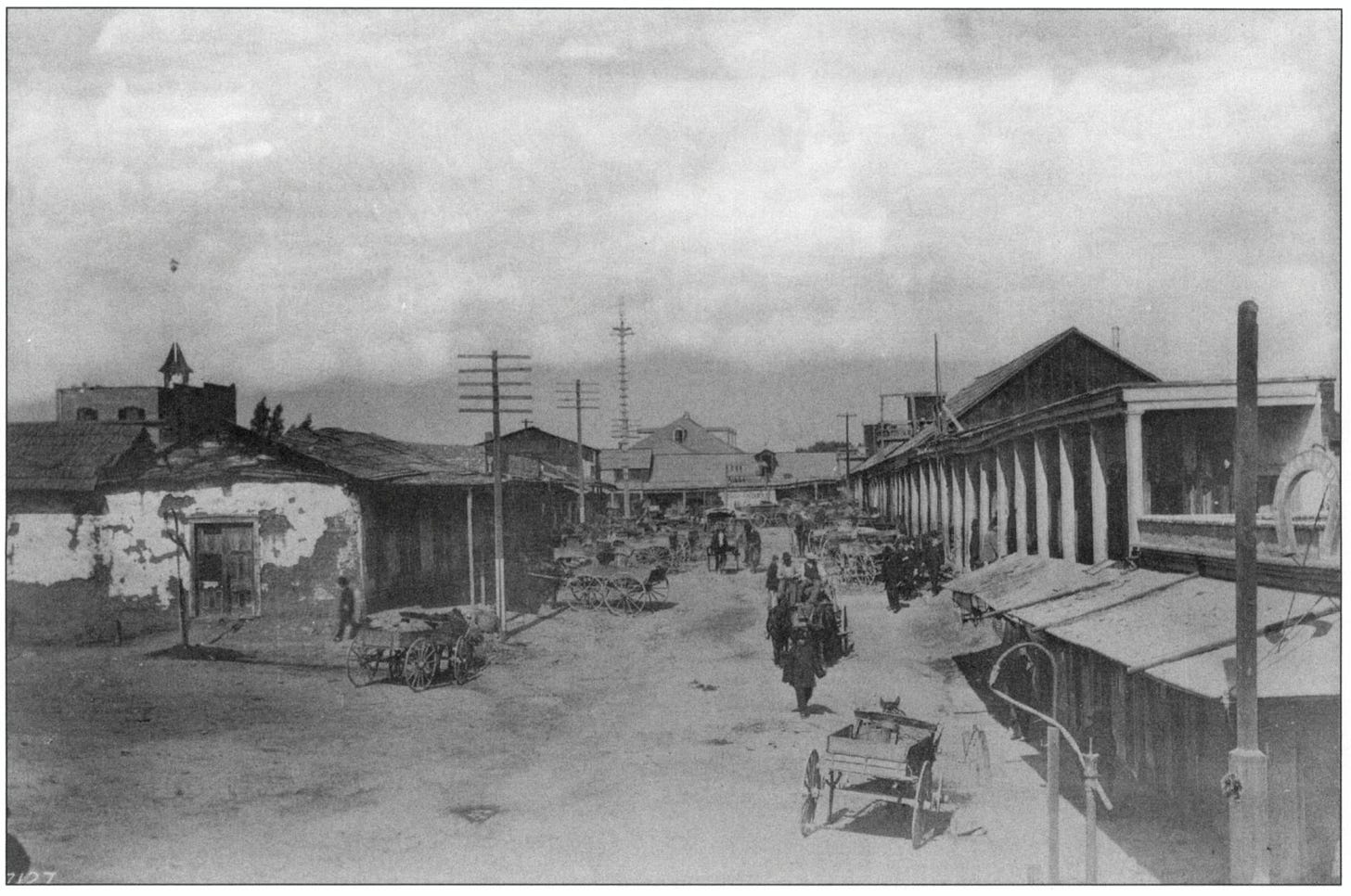

Photo of Calle de los Negros. The adobe building in the back was the start of the 1871 Chinese Massacre.

Much of the early history of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department was wrapped up with vigilante violence. Historical sources throughout the 20th century often argue that the Los Angeles region was violent because of the nature of the territory, the high density of men, and “the transience of the population,” as one scholar says.

It’s difficult to tell how much of this is romance and how much is reality. California’s early days as a state were marked with incredible violence imparted by the U.S. military against both indigenous people and Mexicans living in California.

From a practical matter, early Los Angeles sheriffs did not enjoy a lot of gravitas. If the vigilance committee (usually consisting of all the wealthier white men in the town) decided that someone should be punished, then it would happen whether the sheriff wanted it or not.

Take, for example, the trial and execution of Felipe Alvitre and David Brown who were tried and convicted of murder in 1854. There was a debate between the legitimacy of the legal procedures (conducted by Judge Benjamin Hayes, the first judge in Los Angeles County, who wanted to limit vigilante violence and impose a more restrained, judicial approach), with members of the Anglo public calling for a public hanging. The California Supreme Court issued a stay of execution for both men, but Alvitre’s stay was literally lost in the mail. Sheriff James Barton executed him. A week later, Judge Hayes got the stay.

Brown received his stay in time and was spared until a lynch mob pulled him from the Los Angeles jail and hung him anyway. One of the vigilante members was the mayor himself, who resigned from his position just so he could do the deed. The sheriff? Well, what could he do?

It makes sense that historians would seek to exalt the role and history of sheriff given that sheriffs were lacking in authority for the early decades of their existence. This was particularly true in the West. There was no money for courts, no august buildings, no forensic science, no investigative techniques – none of the hallmarks of modern policing or detective work (or even law).

One of the famous early Los Angeles sheriffs was James Barton, who would eventually die in a shoot-out. Sheriff Barton’s most notable characteristic was his lack of self-awareness and caution. He was described as “brave but reckless” by a contemporary. He also, according to chronicler and vigilante Horace Bell, wasn’t great with the ladies. According to Bell, Sheriff Barton upset a man named Andres Fonte when Fonte came across Barton engaged in domestic abuse:

Our angel Barton was an unmarried man and lived in illicit intercourse with an Indian women, who, for some alleged ill treatment, left him and went to a family residing on the east side of the river. Barton went for her and on her refusal to go with him violently seized and was dragging her away, when Andres happened to be riding along the road, interposed in favor of the woman, and Barton was constrained to desist.

Barton’s demise came, so they say, as he lived. In 1857, Sheriff James Barton led a posse after some alleged outlaws, a group which included Andres Fonte, the man who had thwarted Barton’s attempted kidnapping. They were ambushed in a canyon, and Barton was killed, along with a couple of other men in his posse. Allegedly, Fonte shot Barton in the head just as Barton, in his last gasp of life, fired shots at Fonte.

This incident inspired a rash of vigilante revenge violence, encouraged by the state legislature, which approved $3,000 for the LA Board of Supervisors and $2,000 for San Bernardino to hunt down and murder Barton’s killers. In essence, vigilantes were rewarded with state funding.

Not everyone was pleased with the reign of vigilantism. Judge Hayes, for example, wrote two editorials against vigilance committees after the violence stemming from the death of Sheriff Barton. In his view, vigilanteism was counterproductive to justice.

But the violence persisted. In 1863, a group of 300 men (allegedly) broke into the Los Angeles jail with pickaxes and sledgehammers in order to lynch all of the inhabitants. Sheriff Tomas A. Sanchez formed a posse to protect the jail from further mob violence. The vigilance committee issued a statement declaring their intent to “aid and assist” the Sheriff “in the pursuit and arrest of escaped convicts and of all persons accused of crimes.” (Sanchez later joined a militia devoted to the Confederacy once the Civil War began.)

Vigilantism was also incredibly popular in more rural areas, especially mining towns. Take, for example, Placerville, known as “Hangtown” by all popular 19th-century accounts of the place. (Historical documents show it was literally just called “Hangtown.”) A gold mining town, the city was infamous for vigilante justice usually against alleged thieves, which was a big fear during a time when every man was trying to pan some gold for himself and not share it. This spring, the city council finally removed the noose from their city logo but opted to keep the name “Old Hangtown” on signs throughout the city.

The 1871 Chinese Massacre

The LASD’s version of the terrible massacre of 1871 credits the sheriff, James Burns, with intervening in an ongoing “riot and massacre of Chinese people,” gaining control of the situation and “taught the wild frontier town a lesson it would never forget.”

The 1871 massacre of at least 19 Chinese immigrants (10% of the Chinese population of Los Angeles at the time) was both in alignment with the vigilante justice traditions of the day and a reflection of the intense racism in the region. Most of the contemporary accounts are thoroughly tainted with anti-Chinese racism, enough so that they hardly seem representative of the actual events.

What is known is that Chinese immigrants slowly increased in number after California became a state, providing a steady source of labor. By 1870, anti-Chinese sentiment, which began with xenophobic screeds blaming Chinese workers for stealing Anglo jobs, turned to murderous racism. 1870 also happened to be the year the California legislature considered the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which guaranteed the right to vote to men regardless of race. An editorial in the Los Angeles News complained that such an amendment would allow a “horde of idolatrous barbarians” to vote: “[W]e might soon see them at the polls, in the jury box, upon the bench, and in our legislative halls.” (California didn’t ratify the 15th Amendment until 1962. Not a typo.)

Most accounts agree that the massacre started the afternoon of October 24, 1871, with some sort of feud, during which a man named Ah Choy was shot. An unknown shooter shot some Anglo men, killing one, which sparked a murderous riot. The Anglo man – a popular saloonkeeper –who died from his gunshot wounds was, in some accounts, serving as a volunteer police officer and has run outside (because of course, he was in the saloon at the time) to investigate the shooting of Ah Choy.

The Anglo vigilantes dragged Chinese residents forcefully from their homes, shot them if they tried to escape, and lynched many on the spot. Anglo citizens then looted the homes of the Chinese victims, stealing jewelry, gold, and cash. They victory-marched through the town showing off their loot. Some accounts put the mob at 500 men.

While law enforcement tried to control the mob the next day, most people were reluctant to testify against their fellow white men and anyone who was Chinese couldn’t testify at all. And, contrary to the praise the LASD heaps upon itself, it does not appear that the sheriff and his men (of which there were only 2) were very effective at controlling the mob. There were 37 indictments and 15 convictions, but the California Supreme Court overturned all of the guilty verdicts.

Some historians and pundits argue that this horrible massacre led to an increased police presence and improved justice system in Los Angeles. Most agree it was only the beginning of an awful history of racism against Chinese-Americans. Contemporaneous news accounts reflect that anti-Chinese sentiment actually increased after the massacre, leading to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

So, was this horrific event a turning point for the LASD? Was it the moment when state-sponsored police forces wrested control from vigilante mobs? I will let you decide.

An overly long note on this history: Originally, I thought I might proceed through the LASD history sheriff-by-sheriff, the same way we learn about the presidents in elementary school. But, I realized that this would be a mistake. One of my central theories of sheriffs and sheriff history is that such histories are used by sheriff departments to invent a narrative where sheriffs are moving towards progress, which is always more policing. Think about the array of photos marching primly down a hall, naming each man who held the office of sheriff. We use these men to assert legitimacy, one following the other in an unbroken line. While of course the reigns of control matter, to simply write a history of the LASD using that as a map struck me as replicating the same problems I seek to question.

So this history will not proceed in that way with a series of dates and names. Instead, I am going to arrange this history by idea and theme (or whatever strikes my fancy), which means there may be some back-and-forth. For those of you who are disappointed and want to know who when sheriffs and during what date, don’t worry, you can look it up online.

Next week: The LASD and the “hobo”

Sources:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41172258

https://www.lapl.org/collections-resources/blogs/lapl/chinese-massacre-1871

https://www.biblio.com/reminiscences-of-a-ranger-by-bell-horace/work/190542

https://www.kcet.org/shows/departures/tomas-a-sanchez-the-californio-sheriff-of-los-angeles