How Local Law Enforcement Collaborates with ICE

February 6, 2026

This week, “Border Czar” (not a real job, i.e., neither created nor vetted by Congress) Tom Homan, who has never met a delivery bag full of $50,000 he didn’t like, said that he would focus on arresting and jailing the “worst of the worst,” primarily by working with local law enforcement to arrest people already in jail. Coordination between local law enforcement and ICE is multi-faceted and hard to track.

Here, I wanted to lay out some groundwork for people to better understand some of the systems of local collaboration. As a preface, as readers of this are likely aware, the administration is not being very transparent about their methods; data collection is very poor; and so much is happening that it’s not always clear to me how and if “laws” are being followed. Most local collaboration between police agencies is informal, meaning it is governed by tradition, discretion, and something like “good faith.” (“Just trust us!”) As a result, it’s a system prone to abuse.

Further, collaboration between local law enforcement and ICE does not change the due process requirements for immigration arrests. People accused of being deportable are entitled to hearings, including a hearing to demand release from detention pending a decision on their case. But, once people are in detention, it is harder for them to defend their case. In all cases, people can be transferred to immigration detention simply for charges, not conviction. In other words, a person may get taken by ICE and sent out of the country before prosecuting attorneys have a chance to even try the case.

287(g) agreements

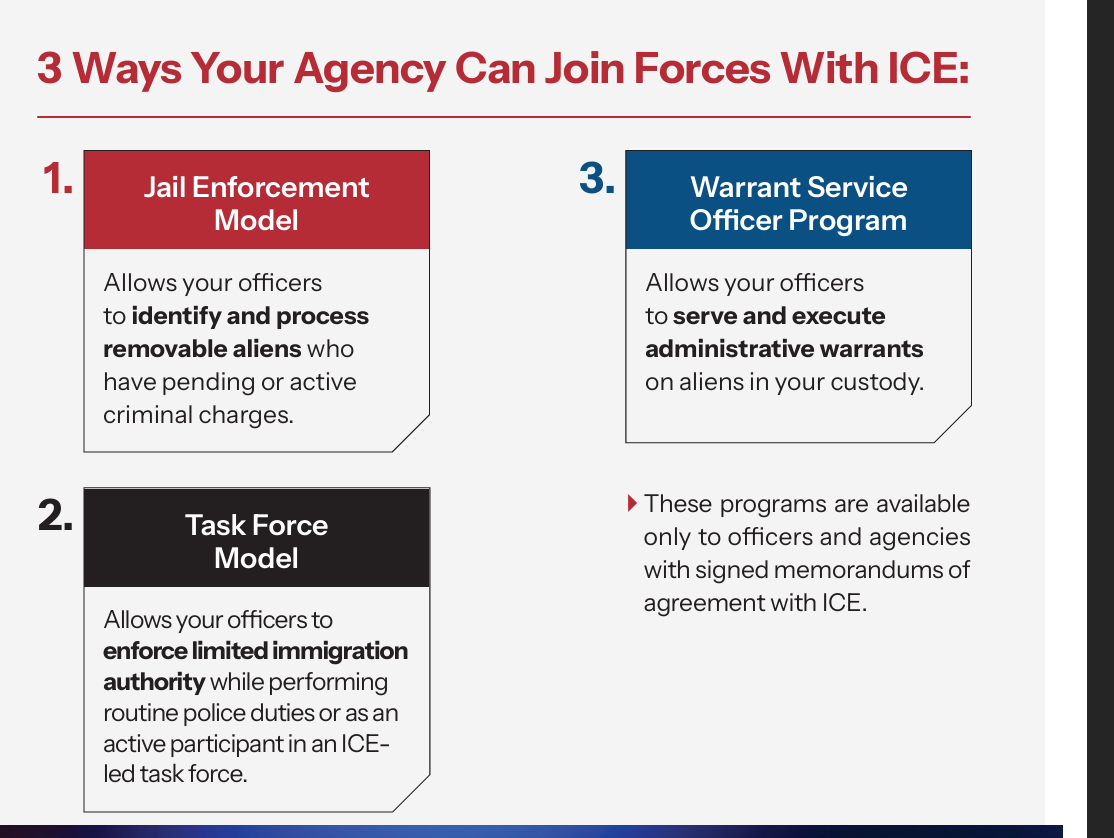

One way local law enforcement can collaborate with ICE is through 287(g) agreements. These are formalized agreements that enable local law enforcement to act like immigration agents. There are three types per DHS: the Jail Enforcement Model, the Warrant Service Officer Model, and the Task Force Model.

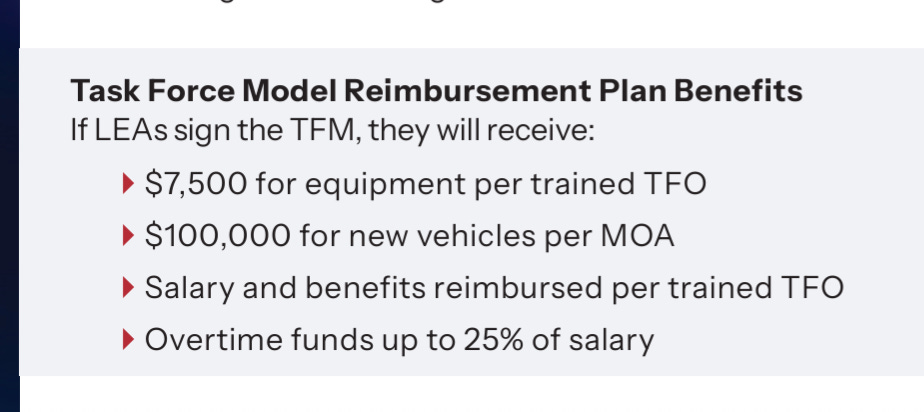

“Task Force” agreements require only a 40-hour online training. This is why everyone loves it. DHS has also said it would compensate agencies for 287(g) participation. Some law enforcement leaders have called it a “bounty” outright. I do not know if these payments have happened or how.

This “task force” version is not only the easiest but the broadest. It is a 287(g) agreement that allows local police to arrest and jail people for alleged immigration violations only. Prior to 2025, this agreement had fallen out of use (but was never ended) because of Joe Arpaio, who used his task force agreement to justify massive numbers of traffic stops to question Latinos about their immigration status. Agencies with 287(g) task force agreement are basically using it to racially profile on a massive scale, intentionally so. In fact, when anti-immigrant groups began to argue for “task force” agreements, this was their goal – to use traffic stops as a way to sweep the community for people to deport. When local police pull someone over, they search their name in NCIC on the terminal in their squad car. Because at least some administrative warrants (requests to hold by DHS) are in NCIC, they are available for local law enforcement to see and use to justify an arrest.

The other two versions of 287(g) operate inside jails. Both allow sheriffs to serve administrative warrants and detain people for potentially being deportable. One version allows for deputies inside a jail to question people as to their immigration status and conduct other interrogations.

There are over 1,000 287(g) agreements across the country, and you can see a list here. Some states, like Texas and Florida, require every sheriff (at least) to enter into a 287(g) agreement. Other states have outlawed participation or are considering outlawing it. To be clear, in most states, these are voluntary programs and states determine via legislation whether they are required or not.

I want to flag a new program that specifically targets Indian law enforcement agencies called the “Tribal Task Force Model.” It is new to me, and if you know something about it, please let me know. (There are no participants to date.)

Most of the other collaborations between local law enforcement and ICE happens inside jails. Homan and most sheriffs really like using local jails as a funnel for deportation because people inside jails are easily locatable (you aren’t going anywhere) and have been processed at the point of arrest. To add, local laws that require or encourage the arrest and detention of people (even those accused of misdemeanors) are making it easier to deport immigrants. In some states, you can be booked into jail for a traffic infraction. We know that local police racially profile in traffic stops; so many people arrested are more likely to be Black or Brown and, thus, more likely to be immigrants.

Homan will make it sound like people in jails are major criminals, but they are not. Historically, most people deported under 287(g) were people accused of driving under the influence, which is a crime, but, to my knowledge, not eligible for the death penalty, which is what deportation is for some people.

Basic Ordering Agreements

Recently, reporting from Minnesota has indicated that Tom Homan is attempting to skirt state law using Basic Ordering Agreements. Basic Ordering Agreements were pioneered in Florida as a way to get around legal vagueness on whether detainers are sufficient to hold people for ICE. In the words of the National Sheriffs’ Association, under a BOA, a person is “detained by the local jurisdiction under the color of federal authority.”

A BOA is really a procurement contract, which means, in essence, that the people under the BOA are treated like cargo. ICE usually pays $50 for the sheriff to hold people 48 hours past their release date in order to pick the person up. Are these BOAs actually legal and do they get around local non-cooperation laws? It’s an open question that hasn’t been decided, although groups like the ACLU say no.

A few Minnesota sheriffs have been sued for honoring detainers, so converting to a BOA system is likely Homan’s effort to avoid lawsuits. There’s a long backstory on how Homan, sheriffs, and anti-immigrant groups have collaborated for decades on compelling local sheriffs to work with ICE and how to get around “sanctuary” laws. (In short, sanctuary laws are laws that prohibit some forms of local collaboration with ICE; they vary greatly.)

Biometric Databases

When you are arrested and booked into jail, deputies take your fingerprint and other information. They run this information through a national database that includes a dump of open warrants from agencies, including federal ones. Thus, if you have an open warrant for something (like failure to appear), you might get transferred to another jail. (I colloquially call this the “men in vans” role of ICE, which is most of what they do.)

The same applied for people who might be deportable; deputies at the point of arrest can see if you might be deportable. This program used to be called Secure Communities and was touted as “ICE in every jail.” Under Obama, it became the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP) because it was supposed to be “limited” to people accused of felonies punishable by over a year. (If you know anything about prosecutorial discretion, you know that this is not hard to game.) As far as I know, Trump got rid of all priorities, so I assume every person arrested is open game.

Once someone is flagged by a database, the agency has a few choices. Some jails have embedded ICE agents at a desk in the jail. They basically check every single booking to see if they are deportable. If there’s a 287(g) agreement, the agency can just detain the person (already in a cage) and will usually call ICE to pick them up and transfer them to immigration jail. Some jails house people for ICE (for a fee), so they might stay in the same facility.

If there is no 287(g) agreement, the agency has a few options. This is where “detainers” come in. Detainers are a request to hold someone for 48 hours for ICE to pick them up; that’s the kind of warrant that pops up in the system if someone is potentially deportable. In some states, it is not legal to hold someone beyond their release just for ICE. Some agencies will hold people for 48 hours or less for ICE to come and pick people up. Some agencies, including those in states that do not allow collaboration with ICE, will call or email their local ICE office and notify them that a person is in their custody. Some agencies will allow ICE to sit outside the jail and pick people up as they walk out – this happens in every state, including “sanctuary” states like California. DHS can also get a judicial warrant, show up at the jail, and take the person in question to immigration jail. (DHS doesn’t like doing this because they are kinda lazy.) Jail rosters are also online and public, so DHS can also comb those. (Again, the lazy factor.)

These databases, as you might expect, are riddled with errors. Plus, ICE does not pick all those people up. So, there’s a great deal of arbitrariness in the system. Finally, people do not have to be convicted to be eligible for deportation; they may simply be accused (not even formally charged in many cases). ICE does pick up people from state prison as well; these are people who served their sentence and then get deported, often years and years later.

This collaboration isn’t very transparent because it happens inside jails, which is why local and federal police like it. (No protestors allowed.) Here’s how it happens. You are driving along and get stopped for speeding. The arresting cop checks his computer and sees that there is an administrative warrant because you overstayed your visa. The cop arrests you, books you into jail, and then lets ICE know you are there. Maybe ICE comes to get you; maybe they don’t. Let’s say then you make bail. As you walk out the door, ICE is there with a van. Or, even worse, you pay bail, go home with your court date, and then ICE shows up at your door some other day. You would have no way of knowing which one will happen.

As another example, perhaps police arrest a group of teenagers standing around, ostensibly for loitering. They take them back to the station and run their names in NCIC to see if they scooped up anyone with an open warrant or criminal record. Turns out one teenager immigrated with his family from another country and is awaiting the determination of an asylum claim. Police decide to call ICE; ICE then arrests the teenager and goes on to locate and arrest the family. (Historically, police would probably not call ICE for this, but they could and probably would under the current administration.) As an aside, if you are in the middle of litigating some sort of immigration claim, an arrest is considered a ding against you, even if you were arrested for plainly racist reasons and never even charged with a crime.

Other collaboration

There are also other programs that operate with local agencies. Some are joint task forces, like a fugitive task force, that will include local and federal agents.

Another program I have seen pop up increasingly frequently, but confess I don’t know a lot about, is the Criminal Alien Enforcement Program (CAP). Whatever the method, the result is pretty much the same. ICE agents come in the van, pick you up, and now you are in immigration jail.

Flock data

I read this, published by 404, that talks about Flock data being shared with DHS. My understanding at this point is that there are no real laws to govern this. Flock allows participating agencies to join a national network, but some agencies can opt out. However, it seems that ICE simply calls a friendly agency to check their Flock data. It’s not clear to me how other cooperation agreements intersect with this kind of massive surveillance and data collection. (When most of these collaborations were established, there wasn’t as much surveillance, so there aren’t laws to catch up.)

I hope this is somewhat helpful to people. I am interested to hear about other experiences people have had in the community because I am sure this is not exhaustive. In summary, the criminal and immigration systems are deeply, perhaps now inextricably, intertwined. It is very hard to avoid immigration arrest once you are in the criminal system dragnet. I wrote about the police state of Florida here, which gives a primer on both how these systems are intertwined, the anti-immigrant lobbyists behind most of these laws (they aren’t “accidents”), and why anyone can become a “criminal.” The entire system runs on the alleged “sound discretion” of the people involved, and we are seeing some of the worst possible outcomes.

Excellent piece!

One flag jumped up near the end when talking about people being bailed out, then arrested when released from the jail. The problem is, whoever signed that bail agreement, would be liable for the full amount once the ICE-detained and/or deported individual didn't show up to their next hearing. That could be family, loved ones etc. that may have put their house or other valuable assets up for collateral. Not sure if this is a possibility, but it seems like it could be a nightmare, especially if the individual's family got snared by ICE while trying to work out the issue with the courts.

[My assumption is, we can all agree nearly everything else you mentioned was already a huge red flag!]

Thx for this.